The title of the exhibition, Iconoclastic Fury, evokes a range of historical and contemporary associations, but it primarily relates to Jarram’s development as an artist. That journey begins in Morocco, where he grew up within a visual culture shaped more by decoration than by figuration. The depiction of God and living beings is not part of Islamic tradition, which meant artistic expression was largely defined by geometric patterns and decorative linework. But Jarram felt a strong urge to depict the world and the people in it. He sought new visual references and found them in 17th-century Dutch painting—such as the landscapes of Jacob van Ruisdael—and in Christian depictions of Jesus and Mary, along with other biblical scenes. From these paintings he “borrowed” motifs, as he puts it: “To make something your own that doesn’t belong to you.” In Jarram’s case, that was the image. In his drawings, often made in charcoal and pastel, Islamic symbols blend with Dutch landscapes, and biblical figures merge with surrealist elements. Like an ethnographer, he explored the meanings behind all these images, while simultaneously imbuing them with new layers of meaning.

Victory of Figuration

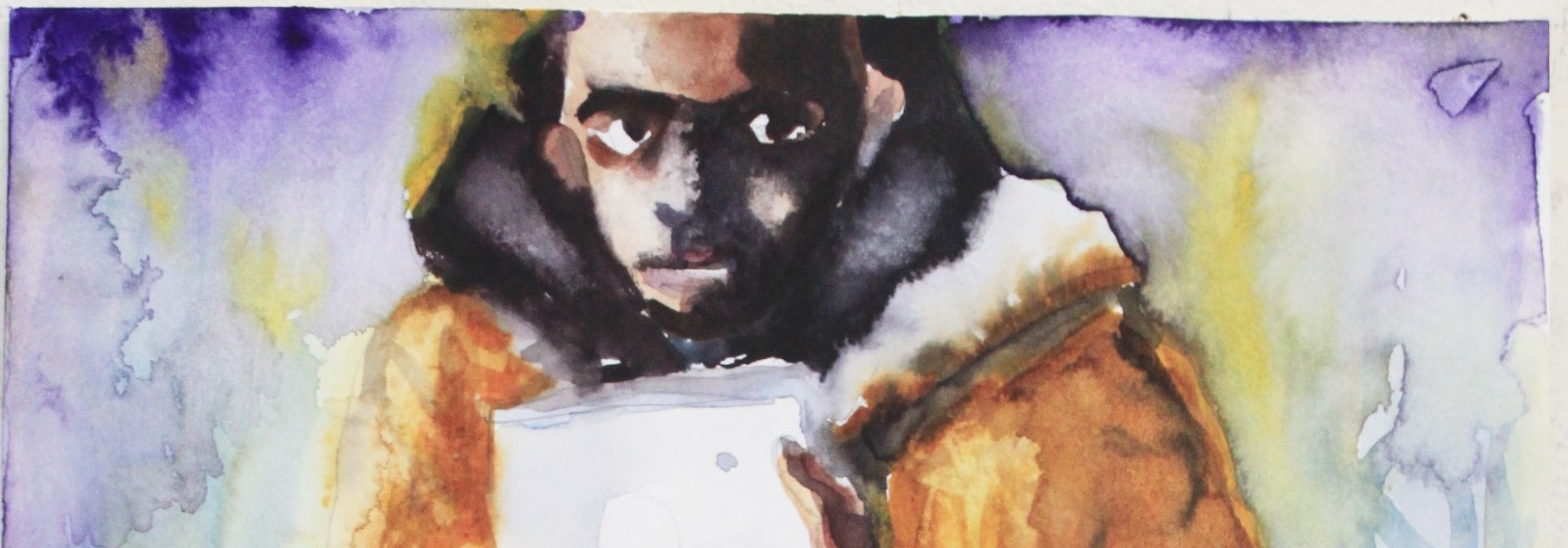

Conquering figuration long felt like a struggle, but around 2015 a turning point came. The battle was over, and all the images that had been hiding in the corners of his mind began to flow out. He started creating portraits of people, mostly in watercolor. He focused on subjects he felt deeply connected to, such as the many refugees trying to reach Europe from Africa—on their way to the promised land, searching for new possibilities, just as he once had when he left Casablanca for Enschede.

This period also marked the beginning of his Moroccan Youngsters: portraits of youths with Moroccan roots. The selfies these young people post on Facebook serve as the inspiration for this ongoing series. They are psychological portraits of boys and girls searching for posture and identity in a turbulent era.

Building Monuments

But the title Iconoclastic Fury is not only about the artistic journey Jarram has taken. It inevitably brings to mind the destruction of images, like what happened in the 16th century during the Reformation, and what is still happening today with alleged national heroes being pulled from their pedestals. Through images, history not only gains a face but is also made. And sometimes that history needs to be revised or supplemented. “In fact, I am constantly working to correct history in my art,” says Jarram. He does this not by tearing down images, but by building new monuments. Like with the pastel Le soldat inconnu (2008), which gave a face to the Moroccan men who fought for freedom during World War II. Or with his recent watercolor A tribute to the dead (2020): an ode to Sudanese poet Abdel Wahab Youssif, who died crossing from Africa to Europe, on his way to a new life and the beautiful new things he might have created.

The exhibition Iconoclastic Fury features works created between 2007 and 2020. From early large surreal pastel drawings blending various motifs, through Dutch landscapes enriched with Islamic motifs, to recent watercolors of Moroccan youngsters and Africans searching for a better life.